Conventional computers store information in a bit, a fundamental unit of logic that can take a value of 0 or 1. Quantum computers rely on quantum bits, also known as a "qubits," as their fundamental building blocks. Bits in traditional computers encode a single value, either a 0 or a 1. The state of a qubit, by contrast, can simultaneously have a value of both 0 and 1. This peculiar property, a consequence of the fundamental laws of quantum physics, results in the dramatic complexity in quantum systems.

Quantum computing is a nascent and rapidly developing field that promises to use this complexity to solve problems that are difficult to tackle with conventional computers. A key challenge for quantum computing, however, is that it requires making large numbers of qubits work together—which is difficult to accomplish while avoiding interactions with the outside environment that would rob the qubits of their quantum properties.

New research from the lab of Oskar Painter, John G Braun Professor of Applied Physics and Physics in the Division of Engineering and Applied Science, explores the use of superconducting metamaterials to overcome this challenge.

Metamaterials are specially engineered by combining multiple component materials at a scale smaller than the wavelength of light, giving them the ability to manipulate how particles of light, or photons, behave. Metamaterials can be used to reflect, turn, or focus beams of light in nearly any desired manner. A metamaterial can also create a frequency band where the propagation of photons becomes entirely forbidden, a so-called "photonic bandgap."

The Caltech team used a photonic bandgap to trap microwave photons in a superconducting quantum circuit, creating a promising technology for building future quantum computers.

"In principle, this is a scalable and flexible substrate on which to build complex circuits for interconnecting certain types of qubits," says Painter, leader of the group that conducted the research, which was published in Nature Communications on September 12. "Not only can one play with the spatial arrangement of the connectivity between qubits, but one can also design the connectivity to occur only at certain desired frequencies."

Painter and his team created a quantum circuit consisting of thin films of a superconductor—a material that transmits electric current with little to no loss of energy—traced onto a silicon microchip. These superconducting patterns transport microwaves from one part of the microchip to another. What makes the system operate in a quantum regime, however, is the use of a so-called Josephson junction, which consists of an atomically thin non-conductive layer sandwiched between two superconducting electrodes. The Josephson junction creates a source of microwave photons with two distinct and isolated states, like an atom's ground and excited electronic states, that are involved in the emission of light, or, in the language of quantum computing, a qubit.

"Superconducting quantum circuits allow one to perform fundamental quantum electrodynamics experiments using a microwave electrical circuit that looks like it could have been yanked directly from your cell phone," Painter says. "We believe that augmenting these circuits with superconducting metamaterials may enable future quantum computing technologies and further the study of more complex quantum systems that lie beyond our capability to model using even the most powerful classical computer simulations."

The paper is titled "Superconducting metamaterials for waveguide quantum electrodynamics." The team of authors was led by Mohammad Mirhosseini, a Kavli Nanoscience Institute Postdoctoral Scholar at Caltech. Co-authors include postdoctoral scholars Andrew Keller and Alp Sipahigil of the Institute for Quantum Information and Matter (IQIM); and graduate students Eun Jong Kim, Vinicius Ferreira, and Mahmoud Kalaee. The work was performed as part of a pair of Multidisciplinary University Research Initiatives from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research ("Quantum Photonic Matter" and "Wiring Quantum Networks with Mechanical Transducers"), and in conjunction with IQIM, a National Science Foundation Physics Frontiers Center supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

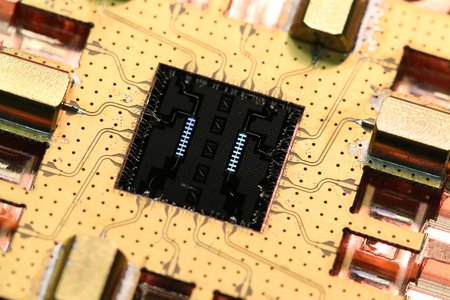

A superconducting metamaterial chip mounted into a microwave test package. The purplish-violet reflection in the center is an optical effect that can seen by the naked eye, and is the result of the diffraction of light by the periodic patterning of the microwave metamaterial.

Credit: Oskar Painter/Caltech

A superconducting metamaterial chip mounted into a microwave test package. The purplish-violet reflection in the center is an optical effect that can seen by the naked eye, and is the result of the diffraction of light by the periodic patterning of the microwave metamaterial.

Credit: Oskar Painter/Caltech