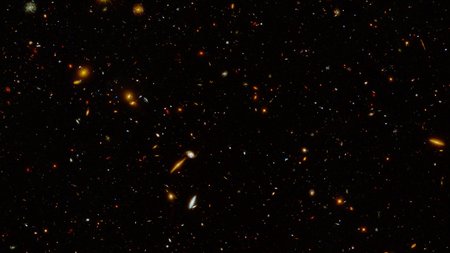

A new image from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope is brimming with distant galaxies in an assortment of shapes. Some are seen face-on and appear oval or as disks or spirals, while others are seen edge-on and look more like cigars. The new image differs from past views of the same field of galaxies in that it now includes observations made in ultraviolet light.

"Ultraviolet light comes from the most massive stars, which are also the youngest and hottest of stars, and it provides a unique insight into ongoing star formation in galaxies both near and far," says Xin Wang, a postdoctoral scholar at Caltech's IPAC, an astronomy center. Wang presented the results June 14 at the 240th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Pasadena.

Wang and his colleagues, led by Harry Teplitz, a staff scientist at IPAC, used the Hubble Space Telescope to survey ultraviolet light coming from distant galaxies in a collection of different patches of sky known collectively as CANDELS, for Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey. They surveyed a large portion of the CANDELS fields, covering an amount of sky equivalent to about 60 percent the size of the full moon. In total, the new program, called UVCANDELS, imaged about 140,000 galaxies and amounted to about 10 days of Hubble time.

The result is the largest ultraviolet Hubble survey of distant galaxies to date. The researchers say the images will ultimately help with a mystery dating back to the early chapters of our universe, to an epoch known as reionization. This is when extreme, or high-energy, ultraviolet light from the first stars and galaxies ionized a fog of hydrogen gas, splitting atoms into charged electrons and protons. After the fog burned away, light could travel through the universe unimpeded, bringing an end to the so-called dark ages. Exactly how this happened is not clear, but by studying the extreme ultraviolet light emitted by distant galaxies, scientists will gather new clues.

"We can't see the extreme ultraviolet light coming from the first galaxies because those photons are absorbed before they reach us," says Teplitz. "We look instead at very similar, or analogous, galaxies that are not quite as far away—11 billion light-years instead of more than 13 billion—to try to understand the physical conditions that enabled the first galaxies to cause reionization."

More information about Hubble can be found at the mission's website.

This image captured by the Hubble Space Telescope shows a region of about 5,000 galaxies located billions of light-years away. The region is located within a cosmic field called the Extended Groth Strip, one of five well-studied fields that were observed in a program called CANDELS, for Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey. In this new view, taken as part of a program called UVCANDELS, ultraviolet and blue optical light have been added into the imagery, in addition to the optical and infrared light observed previously. Ultraviolet light and blue optical light are shown in blue; red light appears green; and near-infrared light is red. The region pictured covers 9 square arcminutes, which is the equivalent of about one percent the size of the full moon on the sky.

Credit: NASA/STScI/Harry Teplitz (Caltech/IPAC)

This image captured by the Hubble Space Telescope shows a region of about 5,000 galaxies located billions of light-years away. The region is located within a cosmic field called the Extended Groth Strip, one of five well-studied fields that were observed in a program called CANDELS, for Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey. In this new view, taken as part of a program called UVCANDELS, ultraviolet and blue optical light have been added into the imagery, in addition to the optical and infrared light observed previously. Ultraviolet light and blue optical light are shown in blue; red light appears green; and near-infrared light is red. The region pictured covers 9 square arcminutes, which is the equivalent of about one percent the size of the full moon on the sky.

Credit: NASA/STScI/Harry Teplitz (Caltech/IPAC)

This movie highlights a new Hubble Space Telescope image of a cosmic field known as the Extended Groth Strip. The image now includes ultraviolet and blue optical light, in addition to optical and infrared light imaged previously. The movie zooms into a smaller region of the field (pictured at top of page) to show more detail.

Credit: NASA/STScI/Harry Teplitz (Caltech/IPAC)

This movie highlights a new Hubble Space Telescope image of a cosmic field known as the Extended Groth Strip. The image now includes ultraviolet and blue optical light, in addition to optical and infrared light imaged previously. The movie zooms into a smaller region of the field (pictured at top of page) to show more detail.

Credit: NASA/STScI/Harry Teplitz (Caltech/IPAC)